World

Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Between 1962 and 2012, 36 States banned trade with Israel. No products, no services, no exchange… radio silence! Well, not exactly. Economists Lorenzo Rotunno and Pierre Louis Vézina found that during this period, Israel exported up to $6.4 billion-worth to those countries. From official to informal flows, the commercial boycott of Israel is clearly less than complete. The authors take a look at the mechanisms behind these secret exchanges and check what remains of the boycott’s intentions.

Since 1948, the 22 member states of the Arab League have maintained a boycott of Israeli companies and goods to show their opposition to the State’s creation. They have not ceased this, and other countries 1 have joined them . Over the years, enthusiasm for the boycott has varied, depending on the political temperature. The Oslo peace process in the 1990s only pacified the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to some extent. Yet in the early 2000s, violence gained the region again with the Second Intifada, leading to the boycott being strengthened.

Enforcing the boycott is not easy. The relationship is asymmetric, since Israel does not mind trading with boycott-enforcing countries. Moreover, most of the latter are Israel’s neighbours, making trade difficult to avoid. The boycott can be seen as a weapon, but is it actually killing trade?

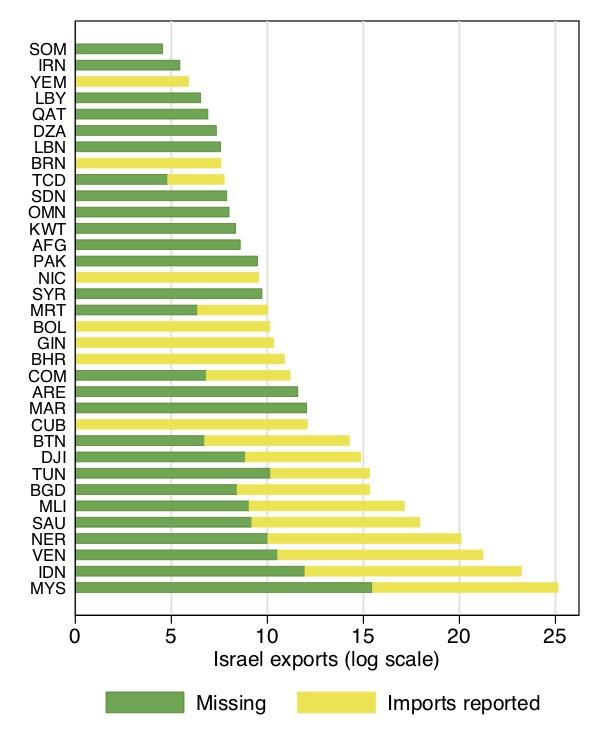

Over the 1962-2012 period, Israel exported more than $6.4 billion-worth of merchandise to boycott countries. The information comes from Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. On both sides, data is inconsistent, with significant gaps in reporting from the importing countries. This means there is a wide discrepancy between what Israel and the boycott countries claim statistically, especially from 2001 onwards. Where are the importers’ missing data? In the shadows of the conflict, boycott-avoiding behaviour is weakening the initial goal.

A particularly telling example of how imports from Israel go unreported is the case of Malaysia. It accounts for the lion’s share of this trade. In 2010, reported exports from Israel to Malaysia reached a peak of $778 million under “Electrical machinery, apparatus and appliances”, mainly from the firm Intel. Malaysia reported matching imports of “Electrical machinery and apparatus”, but carefully concealed them as coming from “Unspecified countries”.

In addition to direct trade, there is evidence of the use of avoidance techniques. Boycott countries can import Israeli goods and services embedded within other countries’ exports via global value chains 2 . How can merchandise be traced? The ban is not only on direct trade with Israel but also on trade with any company doing business with the Hebrew State, a blacklist of 8500 companies! But how can they ensure that the goods and services have no Israeli connection?

The authors of “Israel’s open-secret trade” ask to what extent boycott countries may be fuelling trade with Israel through the use of intermediaries. Israel might be selling unfinished products to a buyer who then processes them and sells them on, potentially to boycott countries. Israel would profit from the added value embedded in the other countries’ exports. The authors clearly show that value is added at a rate no different from that of non-boycott countries.

For example, Saudi Arabia contributed $22million to the Israeli economy in this way, via imports from the US. Given the structure of international supply chains, the boycott cannot be perfectly effective.

Photo by Chuttersnap on Unsplash

The boycott is weakened by circumvention. But it is also an effective barrier to increased trade. According to economists’ estimations, Israel’s exports to boycott countries would have been 10 times greater without it, between 1962 and 2012. It cost Israel 0.3% of GDP, or $800 million. Generally, exports rise in proportion to the economic size and geographic proximity of destination countries. Using this norm as a control, the authors compared it with the Israeli case and found that Yemen, Oman or Lebanon fall well short of the imports that could be expected. So the boycott is curbing trade.

Although the boycott is not foolproof, it undeniably has an effect. It can be circumvented but it still keeps a lot of products out, illustrating the role that diplomacy can play in international trade. In situations of conflict, both economic and political issues define the trade maps of today.