Funding public research to spur private innovation?

© Allesandro Biascioli / Adobe Stock

Public research is often portrayed as a quest for knowledge, while corporate R&D is seen as being driven by market forces. But is this opposition really justified? In a recent study, four economists reveal how a major investment in public laboratories can influence innovation spending across the French industrial sector.

Scientific progress sometimes moves at breakneck speed. When an unknown disease emerged in Wuhan in December 2019, it took barely a year for pharmaceutical companies to deliver the first vaccines. This achievement owed much to substantial financial commitments from governments and philanthropic foundations. Public money, in fact, is frequently a powerful engine of industrial innovation. But how should it be allocated? Should governments directly subsidise firms, for instance through tax credits for private R&D? Or is it more effective to invest in public research, counting on potential indirect benefits? Four economists decided to tackle this question by analysing a major French initiative launched in the early 2010s: the creation of “Laboratories of Excellence”, known as LabEx.

€1.5 billion for excellence

In 2010, France made an ambitious bet. The country dedicated €1.5 billion to strengthening its public laboratories and raising them to world-class standard. To apply for funding, laboratories had to group together into clusters – the LabEx – to present a scientific project and convince an international jury. After two rounds of selection in 2010 and 2011, 170 LabEx were created.

Did this surge in public research funding lead to an increase in private R&D spending? Ideally, one would conduct a lab experiment – like Pasteur injecting a vaccine into one group of sheep and comparing them with an untreated group. Transposed to an industrial context, this would require two sets of companies with similar characteristics, one exposed to LabEx activity and the other not. But such an experiment is impossible in practice: how could some firms be shielded from the influence of major research hubs? The economists therefore opted for a different strategy.

ENIAC, one of the first modern computers, circa 1945. Manufactured by the University of Pennsylvania and used for military purposes. Computing owes a great deal to public research ©US Army photo

An original indicator

The team devised a way to measure the degree to which each firm was “exposed” to LabEx, developing an exposure index based on two criteria. The first is geographical proximity, known to encourage interaction between public labs and private R&D teams. The second is scientific proximity, captured by analysing scientific publications: a laboratory and an industrial sector are considered ‘close’ if they rely on the same scientific journals – researchers to publish their findings, firms to support their patents.

The positive shock of the LabEx

This proximity index allowed the economists to track how R&D departments behaved after the creation of the LabEx, using a technique known as difference-in-differences.

Understanding the “difference-in-differences” method

This method is widely used to assess public policies. Rather than simply comparing before-and-after outcomes, it examines whether the gap that already existed between two groups widens or narrows following an intervention. It offers a way around the lack of randomly assigned control groups.

Take, for example, the 2001 back-to-work support scheme, which offered enhanced guidance to some jobseekers. A retrospective analysis showed that those receiving support took longer to find work than others [1]. Should this be seen as a failure? Not at all. These jobseekers had not been selected at random: they were chosen precisely because they were furthest from the labour market. Even before the policy was introduced, they already needed more time than others to exit unemployment. So the relevant question was whether the scheme widened or reduced the gap. In fact, the analysis showed that the gap diminished after the programme began: the policy had worked.

[1] Fougère, D., Kamionka, T. et Prieto, A. (2010). L'efficacité des mesures d'accompagnement sur le retour à l'emploi. Revue économique, 61(3), 599-612.

The researchers applied the same logic to R&D spending before and after the LabEx initiative, depending on firms’ technological proximity to these public laboratories. If all firms’ spending evolved in the same way, regardless of their proximity to LabEx, the policy would appear to have had no effect. If, on the contrary, firms in the sectors closest to a LabEx see their R&D spending increase relative to others, then we can conclude that LabEx have a positive impact. And this is exactly what was observed.

Up to 2010, wage bills for R&D evolved similarly across firms. After 2010, however, trends diverged. The sectors closest to LabEx saw their R&D wage bill rise more sharply than the rest. On average, the third of firms most exposed to LabEx increased their R&D wage bill by 15% more than the least exposed third. Overall, each euro invested in public research generated €0.80 in additional private R&D spending.

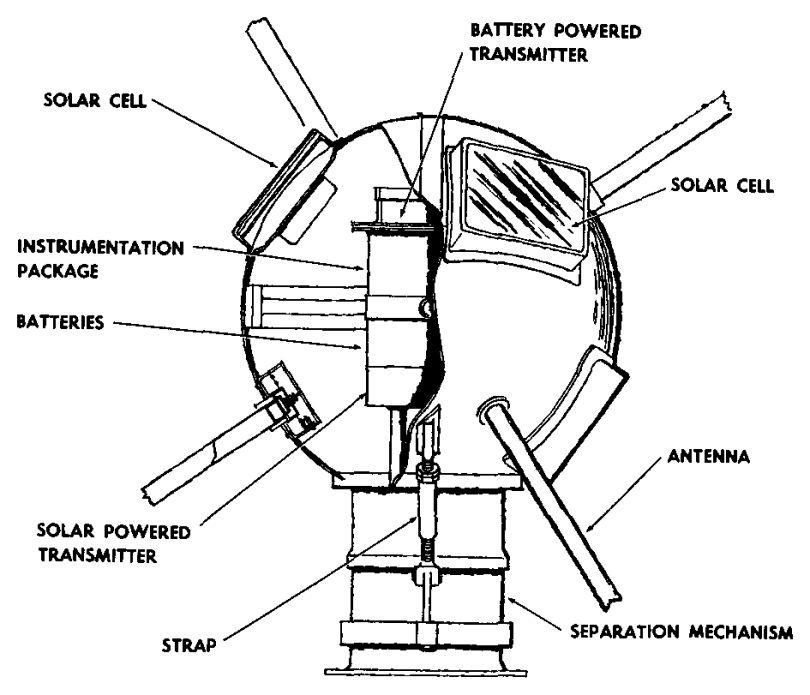

A sketch of Vanguard I, an artificial satellite launched by NASA in 1958. This was one of the first applications of photovoltaic cells, which would be developed considerably as a result of the space race. ©NASA

Formal and informal collaborations

The creation of LabEx did not seem to increase the number of patents filed by the most exposed industries. However, the patents they did file were of higher quality: they were cited more frequently and drew more heavily on scientific literature – a recognised sign of stronger innovation content. But how exactly do these spillovers occur? Through which channels does the financial boost given to the LabEx lead to an increase in R&D in certain industries?

By analysing LabEx application files and data on researcher mobility and start-up creation, the economists identified two main channels. First, formal collaborations: contracts, partnerships and joint patent filings between LabEx and firms. Second, the movement of people: researchers and doctoral students temporarily joining firms, the creation of start-ups, or the hiring of students trained in LabEx-linked institutions. Informal interactions also play a role, emerging through conferences, workshops and other encounters where public researchers and industry professionals meet.

The published study shows that major public research funding stimulates private R&D – provided it targets sectors close to dynamic scientific hubs, unlike broad-brush tools such as research tax credits. To stimulate innovation in private companies, one of the most effective levers remains, therefore, investment in public laboratories.