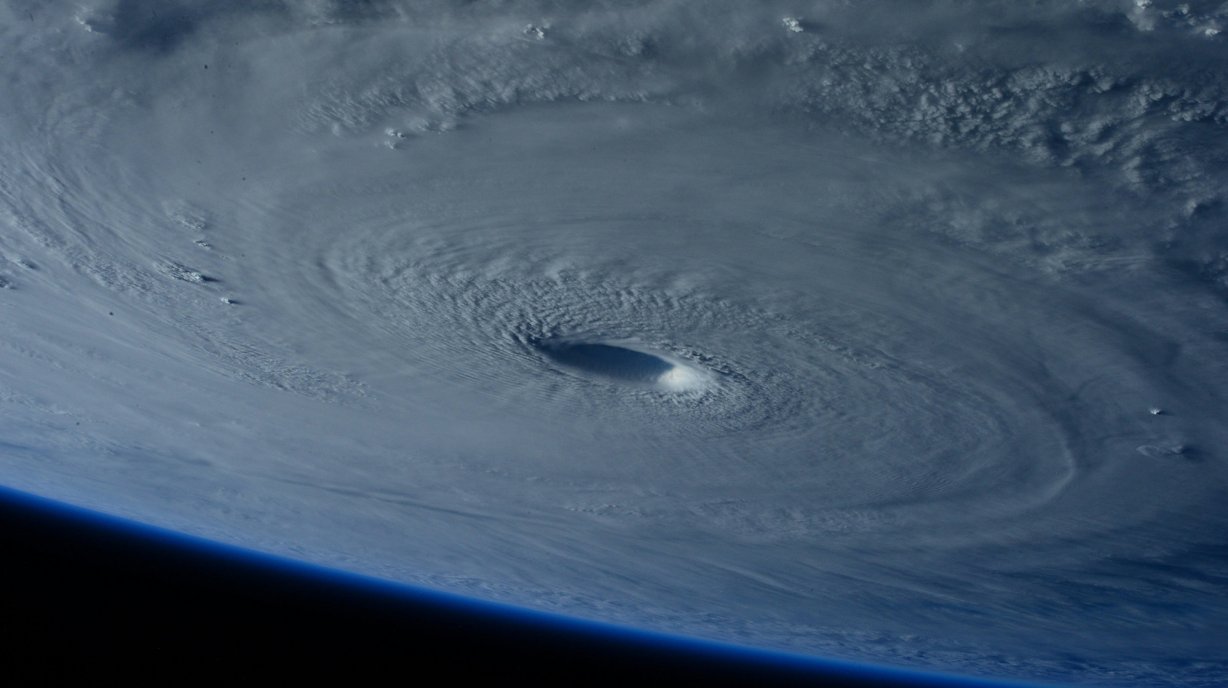

In 2024, a grim record was set: it was the hottest year ever recorded on Earth. The signs of climate upheaval are now visible to all, as global warming manifests itself in a rapid rise in extreme weather events. In theory, the solution is straightforward: we must stop burning fossil fuels. In practice, phasing out energy sources so firmly entrenched in contemporary societies is an immense challenge. To reduce CO₂ emissions, economists — trained in cost–benefit analysis — can help policymakers design strategies that are both effective and socially acceptable.

A Clear Objective: Net Zero

Awareness of climate change has grown rapidly since the establishment of the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) in 1988. Over the years, this has led to increasingly ambitious targets.

Greenhouse Gases and Global Warming

The Earth is surrounded by an atmosphere that traps part of the Sun’s radiation. Thanks to this natural greenhouse effect, the average surface temperature of our planet is around +15 °C rather than -18 °C. This effect is caused by clouds, water vapour, and so-called greenhouse gases (GHGs), chiefly carbon dioxide (CO₂). Since the Industrial Revolution, humanity has burned vast quantities of carbon-based fuels - oil, coal, and gas. The concentration of CO₂ in the atmosphere has risen by more than 40%, driving an average temperature increase of about 1.1 °C compared with pre-industrial levels.

The most recent global target, adopted in Paris at COP21 in 2015, is to keep warming “well below” 2°C. To achieve this, per capita emissions must fall from the global average of 6.5 tonnes of CO₂ in 2022 to around 2 tonnes by 2050 [see “Box: CO₂ or CO₂ equivalent”]. For reasons of fairness, this effort must be distributed according to countries’ different stages of development.

In Burkina Faso, average emissions are below 2 tonnes per person. Yet the country still needs to develop to guarantee a basic level of wellbeing for its population - which will inevitably mean higher emissions.

The Slovnaft refinery, near Bratislava, Slovakia. © Mariano Mantel via Flickr

By contrast, wealthy nations such as the United States, with an average of 18 tonnes per person, must sharply reduce their footprint to meet their fair share of the global effort. In France, the current objective is to reach “carbon neutrality” by 2050, producing no more CO₂ than the country can absorb. But how can this be achieved?

CO₂ or CO₂ Equivalent?

Many gases besides CO₂ contribute to global warming, each with different lifetimes and warming intensities. To compare them, scientists use a common unit: CO₂ equivalent (or CO₂e). For example, one tonne of R134a (a gas used in refrigeration) traps as much heat over 100 years as 1,430 tonnes of CO₂. It is therefore counted as “1,430 CO₂e”. In this article, as in most climate publications, “CO₂” is used as shorthand for all greenhouse gases expressed in CO₂ equivalents, unless stated otherwise.

Back to the France of the 1950s?

For France to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, per capita emissions must fall from around 9 tonnes of CO₂ per year to 2 tonnes. How might this be done? Technologies for capturing and storing carbon are still in their infancy. For now, the only option is to limit emissions — a daunting challenge.

French family in the afterwar period. © United States National Archives

The Carbon Footprint

“The carbon footprint measures the total greenhouse gases (GHGs) we 'emit' indirectly through consumption, including not only domestic production but also goods manufactured and transported from abroad.”

Fanny Henriet "L’économie peut-elle sauver le climat ?" Puf, 2025

To imagine what our daily life looked like when we emitted 2 tonnes of CO₂ per person per year, we need to go back to the 1950sAt that time, life expectancy in France was 73 years for women and 67 for men (compared with 85.3 and 79.4 in 2024). The working week often ran six days and 48 hours; fewer than 10% of each generation earned a baccalauréat (today it is 75%). Only 8% of households had a telephone line (today, 98% of people over 12 own a mobile phone). There were no scanners or MRIs, and only about a hundred intensive care beds nationwide (compared with roughly 6,000 today).

Of course, major technological advances have occurred since the 1950s. Achieving 2 tonnes per capita would not mean reverting to those conditions. But the target remains daunting. Even a climate-conscious household that adopts a frugal lifestyle — limiting heating, choosing low-carbon transport, etc. — would typically only cut emissions by about 40%, which is still far from the goal.

Diversifying the Approach

The solutions must therefore be collective and multi-faceted. It is not just a matter of consuming less, but also of reducing the carbon footprint of what we consume - developing goods, services, and technologies that use less energy through innovation. Between 1995 and 2022, France cut its carbon footprint by around 20%, thanks to a combination of behaviour changes (e.g. lower meat consumption) and technical improvements (e.g. energy efficiency in buildings and industry). Sustaining these efforts will require ongoing encouragement from government. But how can the various measures be assessed and prioritised? Should the state encourage home renovation through tax incentives, or opt for heavy taxation of fossil-fuel heating? Should the country be reforested, or could major industrial sites be decarbonised? Should the price of petrol be raised, electric cars subsidised, or should funds be committed to modernise the rail network?

The Role of Economists

Economists can help weigh up all such options by estimating their “social value” in terms of avoided climate damage. As early as the 1970s, William Nordhaus (awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2018) argued for “integrating climate change into macroeconomic analysis”. This laid the groundwork for the concept of the ‘social cost of carbon’, which was an estimate, “expressed in pounds, dollars or euros, of the damage caused by each additional tonne of CO₂ emitted”. This framework allows comparison of policies by weighing costs against benefits.

Suppose the social cost of carbon is estimated at €200 per tonne of CO₂. Replacing oil boilers with heat pumps at a cost of €50 per tonne avoided is then considered beneficial: the cost (€50) is lower than the benefit (€200). Estimating the social cost of carbon can also guide policy through a “carbon tax” set at that level. By raising the price of carbon-intensive goods and services, such a tax curbs consumption while encouraging producers to develop cleaner technologies.

Yellow vest protest, January 5, 2019. The movement was a reaction to the carbon tax increase, which raises the question of the acceptability of adaptation policies. © Christophe Leung via Flickr

Why a Carbon Tax Alone Will Not Suffice

Research 1 by economists Fanny Henriet, Nicolas Maggiar and Katheline Schubert shows that if France were to rely solely on a carbon tax to meet its reduction targets, the tax would need to rise to socially unacceptable levels — equivalent to more than €1.50 per litre of petrol. Even allowing for “endogenous innovation” - the technical improvements triggered by higher carbon costs - the required tax level would still be very high.

Their conclusion: a carbon tax must be combined with strong support for innovation, to create the necessary alternatives while keeping the transition both economically viable and socially fair.

As Fanny Henriet explains in her recent book 2 , the path to carbon neutrality by 2050 is complex. The cost of CO₂ must rise to curb consumption. Rebound effects must be addressed: insulating homes or building more efficient cars is of limited value if households simply heat more or buy a second vehicle. Technological progress must be supported to deliver genuinely lower-carbon products and services. And crucially, compensatory measures are needed for low-income households, so they are not forced to choose between “the end of the world and the end of the month”. Otherwise, there is a real risk of social backlash.

The route is difficult, but unavoidable if we are to preserve a habitable planet for future generations.

- 1

- F. Henriet, N. Maggiar, K. Schubert, 2016, « La France peut-elle atteindre l’objectif du Facteur 4 ? Une évaluation à l’aide d’un modèle stylisé énergie-économie » Économie & prévision, 208-209(1), 1-21

- F. Henriet, N. Maggiar, K. Schubert, 2014, "A Stylized Applied Energy-Economy Model for France", The Energy Journal 35 (4), 1-38,

- 2

Fanny Henriet, L’économie peut-elle sauver le climat ? Puf, 2025